WITH THE PRODUCTION of Tesla’s mass-market Model 3 now underway, and first deliveries due on Friday, electric cars are about to hit the mainstream. For people driving EVs, it means a raft of changes: plugging in at night instead of hitting the gas station, keeping an eye on a battery meter instead of a fuel gauge, and most importantly, a change in the way they drive.

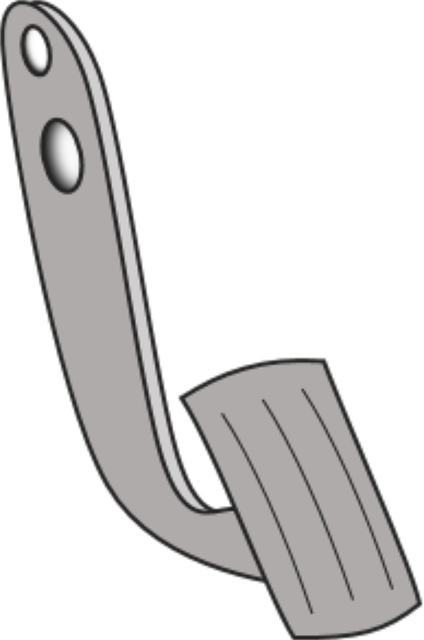

To get the maximum benefit out of driving an electric car, the accelerator (you can’t call it a gas pedal anymore!) controls both the speeding up and slowing down. Pressing the pedal makes the car go, as usual, but lifting your foot makes the car slow down, hard, not coast.

It’s a quirk that takes some getting used to. At first, it can feel like the parking brake has been accidentally left on. But most drivers eventually prefer it because it makes inching forward in traffic much easier than swapping your foot back and forth between pedals.

In a conventional car, brake pads clamp onto a metal disc, with friction converting the kinetic energy of a speeding car into wasted heat. But when electric cars slow down, the electric motor runs as a generator, recovering some of that previously wasted energy to top up the battery. Depending on how much regeneration the software engineers allow when designing the car, the force can be powerful enough to slow the car most of the way to zero, meaning drivers only need to use the brake pedal to come to a full stop.

See Related Post 8 Ways You’re Ruining Your Car Without Realizing It

Nissan will become the first automaker to introduce full one pedal driving in the latest iteration of the electric Leaf, due later this year. It will have an “e-Pedal” option. The pedals will still look the same, but the brake will be pretty much redundant, and computer controls will give the traditional accelerator extra functions. Lifting off won’t just slow the car with regen, but will bring the car to a full stop, and will even hold without rolling backwards on hills.

“I think this is the logical next step,” says Jeffrey Miller, an engineering professor at USC. In a Tesla, owners can already choose exactly how much lifting off the accelerator slows the car on the giant touchscreen. In Chevrolet’s Bolt, drivers have a paddle behind the steering wheel to request extra regeneration, just as they’d tap to downshift and slow down with a sporty automatic gearbox.

A next-gen Leaf driver will never need the brake pedal, although it will still be there, for those “aggressive braking situations” according to Nissan. (In other words, panic stops.)

The advantages of maximizing regen braking are huge. Maintenance costs are lower because barely-used brake pads last for many thousands more miles. There are fewer particles of dust created which pollute the air and waterways. Stopping distances will be shorter too, as the car will start slowing down as soon as the driver begins to lift off the accelerator, rather than when he moves his foot to another pedal.

Most importantly, energy is recaptured rather than wasted, so the range in electric cars is improved. (A Tesla engineer described the experimental regen braking system on the Roadster in 2007, and calculated it was around 65-percent efficient at recapturing energy.)

Regenerative braking does mean electric car owners need to take extra care on slippery roads, because slowing the car aggressively can cause the tires to slip. For drivers, learning to ease off the accelerator rather then jerk a right foot over to the brake means forgetting many years of expecting a car to coast.

The concept isn’t new. Engineers experimented with regen brakes on the very earliest horse-free carriages, and it’s widely implanted on electric trains. A boost in the number of electric cars on the roads is going to make it much more common though, and mean a modern generation of drivers is going to have to forget what they know about pedals and learn a new way to stop.

See Related Post 8 Ways You’re Ruining Your Car Without Realizing It

Credit wired